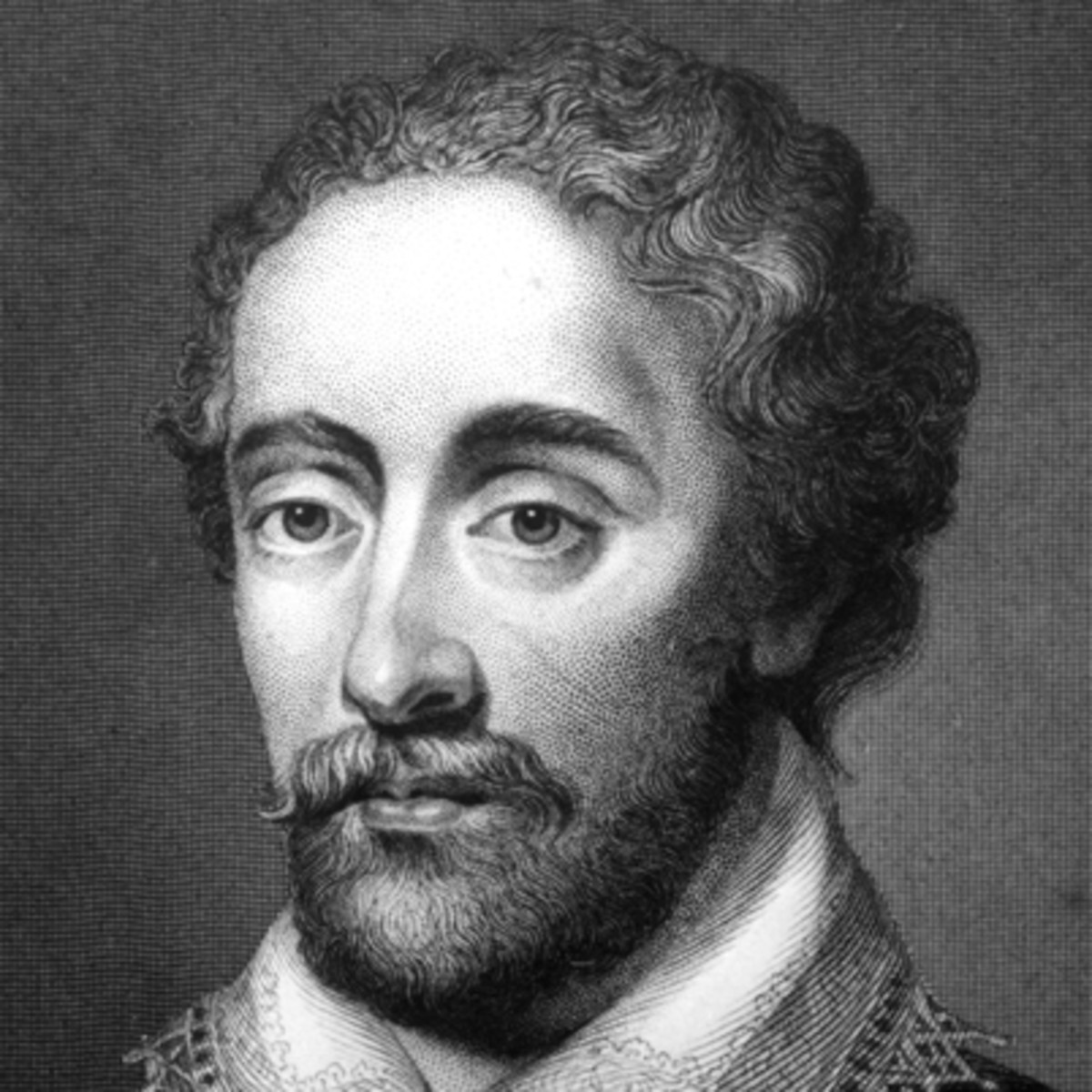

Edmund Spenser’s poetic innovations have formed the basis for many poets throughout British Literature. Among his most popular works is “The Faerie Queene,” a longer allegorical commentary on the political leaders of his time. Most believe that Edmund Spenser was born in 1552, or around that time, and lived during the reign of Elizabeth I. Although “Spenser was born to parents of modest means and station,” (Greenblatt 766), he was able to obtain a decent education, and attended Pembroke College in Cambridge. As an aide to the lord deputy of Ireland, Lord Grey, Spenser fought for England in colonial domination of Ireland, participating in the brutality and political turmoil between the two sister countries. His work is multifaceted; not only does he value and preserve Old English and poetic traditions, such as Virgil’s, he also sought to alter poetry and change forms to create new traditions that have been followed by some of the greatest poets since his time. Spenser’s poetry is a major landmark in the history of literature, just as he intended it to be.

Spencer’s writings are vintage by design. He had “a passionate and patriotic interest in the reformation of English verse,” (Greenblatt), and his work was deliberately antique in order to reform and bring back the old English language. The Norton Anthology says, “In a culture where most accomplished poetry was written by those who were, or at least professed to be, principally interested in something else… Spenser’s ambition was altogether remarkable, and it is still more remarkable that he succeeded in reaching his goal” (766), which was to follow the classical examples of poets such as Virgil and Homer. One article says “Spenser’s ability to imitate multiple authors at once created a plurality of impressions from past traditions in the reader, resulting in a poetic voice which reverberated like a chorus of Classical and Renaissance traditions” (Griffin 1). In one biography from the Poetry Foundation it says:

[Spenser] explains [in a letter to Walter Ralegh] that he has followed the example of the greatest epic writers of the ancient and the modern worlds: Homer and Virgil, Ludovico Ariosto and Torquato Tasso.

The attempt to write a neoclassical epic in English was without precedent… Among the heroic poets named in Spenser’s Letter to Ralegh as worthy practitioners of the form, Virgil was generally regarded as the greatest, and Spenser, like Dante and Petrarch before him, seems to have taken Virgil as his personal mentor and guide. (“Edmund Spenser”)

Virgil’s influence on Spenser’s work can be seen in the way he constructed his epic, “The Faerie Queene.” Jonathan Griffin says, “Spenser parodies and adapts many episodes from the Aeneid to suit his own designs, using Aeneas as a model for many of his own heroes, praising his queen and country in the same fashion as Virgil praised his emperor, and Rome… These Virgilian echoes are molded to Spenser’s own poetic voice and purpose,” (Griffin 4).

Not only does Spenser honor and echo old traditions and language, he creates new poetic structures as well. “The New World Encyclopedia” says:

For The Faerie Queene, Spenser originated a nine-line verse stanza, now known as the Spenserian stanza—the first eight lines are iambic pentameter, and the ninth, iambic hexameter; the rhyme scheme is ababbcbcc. The melodious verse, combined with Spenser’s sensuous imagery and deliberate use of archaic language evocative of the medieval past… serve not only to relieve the high moral seriousness of his theme but to create a complex panorama of great splendor. (“Edmund Spenser”)

Edmund Spenser made it his job to remix and blend the old and the new in his work. By pushing the English language to its limits, Spenser was able to open a world of possibilities to poets and authors of the next generation, such as William Shakespeare, Lord Byron, P.B. Shelley, John Keats, and Alfred Lord Tennyson. He has influenced the writings of even more modern writers, such as J. R. R. Tolkien. This is evident in many of their works that use similar mechanics and schemes that originated in Edmund Spenser’s writing.

The jewel in Edmund Spenser’s crown is “The Faerie Queene,” an epic allegorical poem on living a Christian life of holiness. The series tells a story of several knights, one symbolizing holiness, one chastity, and the others representing various virtues of the Christian faith. In the story, Spenser targets the Catholic Church, writing intense criticism and political commentary through the metaphor. Through his metaphorical writing, he showers his queen, Elizabeth I, with praise and adoration. “The Faerie Queene” was originally intended to be twelve books long, with twelve cantos in each book. Before he completed the epic, Spenser shared the poem with his friend, Walter Raleigh, and explained the allegory in detail in an attached letter. Because the work was left unfinished at Spenser’s death, this letter to his friend has been useful in interpreting the metaphor of “The Faerie Queene,” and the author’s intention, which he said was to “fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline,” (“Letter to Realeigh”). After two attempts to publish his work, Spenser finally found favor with Queen Elizabeth I, who gave him a stipend of 50 pounds per year for the rest of his life and helped him to publish his most popular work.

Spenser also had extreme ideas about Ireland, which he discussed in his piece “A View of the Present State of Ireland.” This piece takes the form of a dialogue between two characters, Iren and Eudox, as they discuss the state of Ireland. Spenser’s employer, Lord Grey, influenced him against the Irish, and he discussed Ireland’s need for reform and the failures of the Irish people. He believed Ireland was in need of reform, and wanted to “cure” the nation of its diseased people and customs. As he worked for the lord deputy, Spenser was involved in the subjugation and domination of these people, and he contributed to the brutality that occurred during the Elizabethan era, including massacres and sieges against the Irish.

In 1594, Spenser married Elizabeth Boyle in Ireland. The following year, a collection of sonnets entitled “Amoretti” was published, alongside another collection of sonnets, “Epithalamion.” The title “Amoretti” means “little loves,” and Spenser wrote this sonnet sequence of love poetry about his romance, courtship, and marriage to his new wife. Sonnets at this time were not usually about “a happy and successful love; traditionally, the sonneteer’s love was for someone painfully inaccessible,” (Greenblatt 985). However, happiness is exactly what he captures in these collections. An epithalamion is an ancient Greek wedding song sung on the threshold of the bridal chamber. The Norton Anthology says:

Spenser follows these conventions closely, adapting them with exquisite delicacy to his small-town Irish setting and native folklore… Traditionally, the poet of an epithalamion was an admiring observer… By combining the roles of poet and bridegroom, Spenser transforms a genial social performance into a passionate lyric utterance. (985)

Spenser’s work again defies the norm, while still maintaining the traditional structure of the poetry.

Spenser and his comrades believed deeply that poetry was of high importance to their country, and they treated their art with a respect and a richness that is difficult to find in today’s world.

Spenser deeply believed that it was necessary to construct an English, Christian Epic. The reasoning for this can be found within Sir Philip Sidney’s work of literary theory, contemporary to Spenser, An Apologie for Poetrie. It is Sidney’s desire to prove to Elizabethan society that the art of poetry is not a waste of time… Upon closer examination, it will become clear that the choices Spenser makes in regards to genre, mode, and style are informed by Sidney’s theories, and by the traditions established by his predecessors. (Griffin 2)

Spenser’s has influenced famous works and authors, and has left a rich legacy. He has heavily influenced poetic structure and mechanics, as well as themes and the lifestyle of the poet. He established precedence and set standards for poetic quality. Sadly, Edmund Spenser was not able to finish the second half of his masterpiece “The Faerie Queene” before he died in 1599, but his great works of fiction, fact, poetry, and prose have been studied and exalted by the literary community for centuries. Spenser is truly a poet’s poet, and has fundamentally changed the culture of the world today.

Works Cited

- “Edmund Spenser.” Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation. Web. 16 June 2015.

- “Edmund Spenser.” Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia (2014). EBSCOhost. Web. 16 June 2015.

- Greenblatt, Stephen, and M. H. Abrams, eds. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 9th ed. Vol. 1. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012. Print.

- Griffin, Jonathan. “Tradition and Imitation in Spenser’s The Faerie Queene.” Journal of Arts and Humanities 2.6 (July 2013): n. pag. Web. 16 June 2015.

- Spenser, Edmund. “Amoretti and Epithalamion.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt and M. H. Abrams. 9th ed. Vol. 1. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012. 985-999. Print.

- ––– “Letter to Raleigh &c.” Letter to Raleigh. The Complete Works in Verse and Prose of Edmund Spenser, n.d. Web. 16 June 2015.

- ––– “The Faerie Queene.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt and M. H. Abrams. 9th ed. Vol. 1. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012. 775-984. Print.